GSoC 2019 | Week 3, 4

Introduction

It’s 2 more weeks into my GSoC working on NumRuby. I worked on adding slicing support and integrate slicing in iterators. Slicing is a crucial feature of a matrix library and must be efficiently implemented as it acts as base for many other operations. So, in order to write an efficient implementation I went through NumPy’s resources on slicing and also through their implementation of slicing. After reading resources on slicing, I came up with an implementation which would use indexing to traverse only those elements which are part of slice.

Slicing

What is slicing?

Wikipedia defines slicing as an operation that extracts a subset of elements from an array and packages them as another array, possibly in a different dimension from the original [source]. For slicing in NMatrix, the definition would be same with “array” replaced with “matrix”. To retrieve a single value, you use indexing. Similarly, to retrieve a collection of values, you would use slicing. A slice could be of lesser number of dimensions that the parent matrix or could have the same number of dimensions.

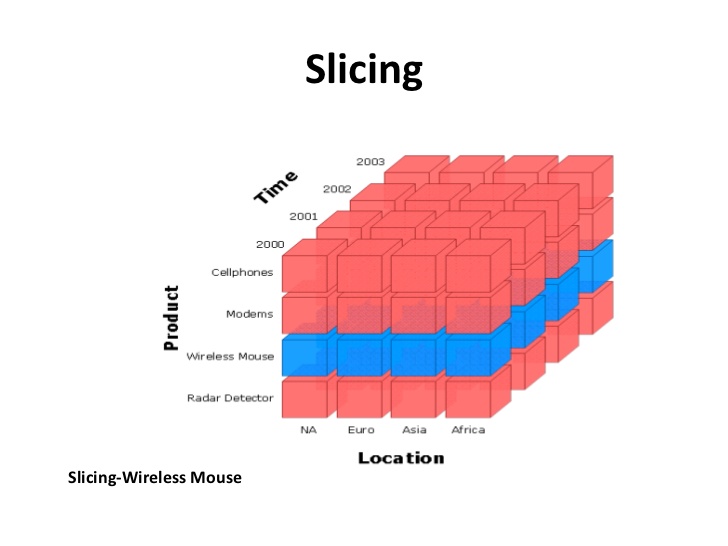

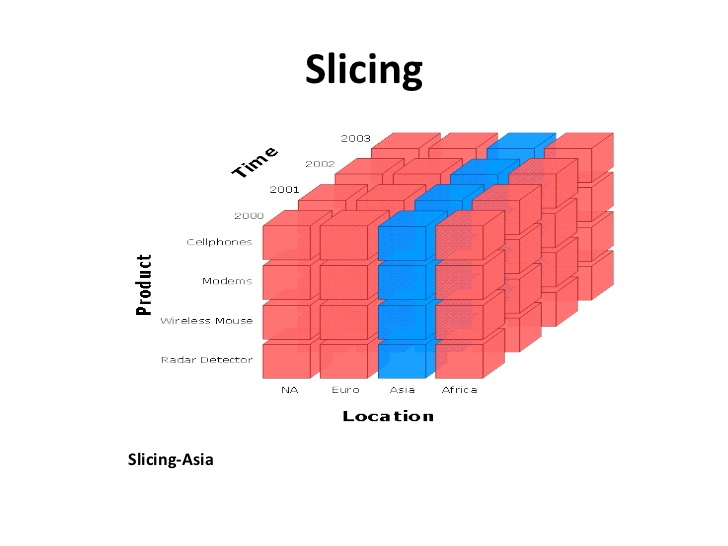

For example, suppose there is a matrix nm having shape [2, 3, 4] and there is a slice x = n[0, 0..1, 0..1] and another slice y = n[0..1, 0..1, 0..1]. x would be of shape [2, 2] and y would be of shape [2, 2, 2]. This is because in x the length of range along first dimension is just one. So, the number of dimensions of slice is number of dimensions of matrix reduced by the number of one length ranges specified. Slicing is used a lot to get the divide data into parts depending on a parameter type or to get data for some particular value[s] of a parameter. For example, the images below gives a good visualization of how slicing works using the very same application.

Images source: https://www.slideshare.net/algum/data-cubes-7923771

If we assume Product as first dimension, Location as second dimension and Time as third dimension, then first image shows a slice (in blue color) along a row for which Product is ‘Wireless Mouse’. The second image shows a slice (in blue color) along a column for which Location is ‘Asia’.

An example on usage of slicing is given below,

pry -r './lib/nmatrix.rb'

[1] pry(main)> m = NMatrix.new [2, 4], [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

=>

[2] pry(main)> m[0, 0..3].elements #slice to get first row

=> [1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0]

[3] pry(main)> m[1, 0..3].elements #slice to get second row

=> [5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0]

[4] pry(main)> m[0..1, 0].elements #slice to get first column

=> [1.0, 5.0]

[5] pry(main)> m[0..1, 1].elements #slice to get second column

=> [2.0, 6.0]

[6] pry(main)> m[0..1, 2].elements #slice to get third column

=> [3.0, 7.0]

[7] pry(main)> m[0..1, 3].elements #slice to get fourth column

=> [4.0, 8.0]

Implementation of slicing

Slicing is having the same syntax as indexing with a minor difference that the comma separated values can also be of type Range and at-least one value must be of type Range else the accessor would just return a single element. So, the slicing function would also be called from accessor function when the given comma separated values correspond to a slice.

bool is_slice(nmatrix* nmat, VALUE* indices){

for(size_t i = 0; i < nmat->ndims; ++i){

if(rb_obj_is_kind_of(indices[i], rb_cRange) == Qtrue)

return true;

}

return false;

}

To check if they correspond to a single element or a slice, a function is_slice was created which would return true if given comma separated values contains a Range type variable. Next, the lower and upper limit of Range value is to be extracted which was done using parse_ranges.

void parse_ranges(nmatrix* nmat, VALUE* indices, size_t* lower, size_t* upper){

for(size_t i = 0; i < nmat->ndims; ++i) {

//take each indices value and parse it

//to get the corr start and end index of the range

size_t a1, b1;

if(rb_obj_is_kind_of(indices[i], rb_cRange) == Qtrue){

VALUE range_begin = rb_funcall(indices[i], rb_intern("begin"), 0);

VALUE range_end = rb_funcall(indices[i], rb_intern("end"), 0);

VALUE exclude_end = rb_funcall(indices[i], rb_intern("exclude_end?"), 0);

a1 = NUM2SIZET(range_begin);

if(range_end == Qnil){ //end-less range

//assign (size_of_dim - 1) to b1

b1 = NUM2SIZET(nmat->shape[i]) - 1;

}

else{

b1 = NUM2SIZET(range_end);

}

if(exclude_end == Qtrue && range_end != Qnil){

b1--;

}

}

else{

a1 = b1 = NUM2SIZET(indices[i]);

}

if(a1 > b1){

//raise invalid range error

}

if(a1 >= nmat->shape[i] || b1 >= nmat->shape[i]){

//raise index out of bounds error

}

lower[i] = a1, upper[i] = b1;

}

}

parse_ranges would take comma separated accessor values as array of VALUE type elements and convert each VALUE to it’s respective lower bound and upper bound values. For example, [0..2, 0, 0...2] would be converted to [(0, 2), (0, 0), (0, 1)] which basically denotes the starting and ending index along each dimension. The reason for parsing comma separated accessor values separately from get_slice function is because it would make the get_slice callable using C data types arguments and this would save the calling function to wrap the arguments in VALUE type if it only has C data type values.

void get_slice(nmatrix* nmat, size_t* lower, size_t* upper, nmatrix* slice){

/*

parse the indices to form ranges for C loops

then use them to fill up the elements

*/

size_t slice_count = 1, slice_ndims = 0;

for(size_t i = 0; i < nmat->ndims; ++i){

size_t a1 = lower[i], b1 = upper[i];

//if range len is > 1, then inc slice_ndims by 1

//and slice_count would be prod of all ranges len

if(b1 - a1 > 0){

slice_ndims++;

slice_count *= (b1 - a1 + 1);

}

}

slice->count = slice_count;

slice->ndims = slice_ndims;

slice->shape = ALLOC_N(size_t, slice->ndims);

size_t slice_ind = 0;

for(size_t i = 0; i < nmat->ndims; ++i){

size_t dim_length = (upper[i] - lower[i] + 1);

if(dim_length == 1)

continue;

slice->shape[slice_ind++] = dim_length;

}

//mark elements that are inside the slice

//and copy them to elements array of slice

VALUE* state_array = ALLOC_N(VALUE, nmat->ndims);

for(size_t i = 0; i < nmat->ndims; ++i){

state_array[i] = SIZET2NUM(lower[i]);

}

double* nmat_elements = (double*)nmat->elements;

double* slice_elements = ALLOC_N(double, slice->count);

for(size_t i = 0; i < slice->count; ++i){

size_t nmat_index = get_index(nmat, state_array);

slice_elements[i] = nmat_elements[nmat_index];

size_t state_index = (nmat->ndims) - 1;

while(true){

size_t curr_index_value = NUM2SIZET(state_array[state_index]);

if(curr_index_value == upper[state_index]){

curr_index_value = lower[state_index];

state_array[state_index] = SIZET2NUM(curr_index_value);

}

else{

curr_index_value++;

state_array[state_index] = SIZET2NUM(curr_index_value);

break;

}

state_index--;

}

}

slice->elements = slice_elements;

}

The above function get_slice is the function which actually fills the elements and other relevant data into slice. This would make use of state_array which stores the comma separated indices for slice elements starting from lowest index to highest index element. The working of state_array was explained in my previous blog. So far, slicing only allows accessor to use Range type variables to specify slice bounds but later it’ll be extended to also support NumPy style range specification which is of type a:b so that it’ll be comfortable for people familiar with Numpy.

VALUE nm_accessor_get(int argc, VALUE* argv, VALUE self){

nmatrix* nmat;

Data_Get_Struct(self, nmatrix, nmat);

size_t* lower_indices = ALLOC_N(size_t, nmat->ndims);

size_t* upper_indices = ALLOC_N(size_t, nmat->ndims);

parse_ranges(nmat, argv, lower_indices, upper_indices);

if(is_slice(nmat, argv)){

nmatrix* slice = ALLOC(nmatrix);

slice->dtype = nmat->dtype;

slice->stype = nmat->stype;

get_slice(nmat, lower_indices, upper_indices, slice);

return Data_Wrap_Struct(NMatrix, NULL, nm_free, slice);

}

else{

size_t index = get_index(nmat, argv);

double* elements = (double*)nmat->elements;

double val = elements[index];

return DBL2NUM(val);

}

return DBL2NUM(-1);

}

nm_accessor_get was also changed to return an NMatrix object consisting of the slice when used for slicing. The above code explains how it is decided if to return a single element or a slice and then call the required function and finally returning the desired result.

Using slicing in iterators

I implemented iterators for NMatrix during last week. These also included iterators along a dimension such as each_row, each_column and each_layer. These “along the dimension” iterators were only implemented for 2d matrices as they can’t be implemented for n-dimensional matrices without slicing.

Now that slicing has been implemented, iterators along dimension for n-dimensional matrices can be implemented. This was done by first implementing a generic function nm_each_rank which takes the matrix and index of dimension and traverses all the slices along that dimension. The working of nm_each_rank was explained in the previous blog.

VALUE nm_each_rank(VALUE self, VALUE dimension_idx) {

nmatrix* input;

Data_Get_Struct(self, nmatrix, input);

size_t dim_idx = NUM2SIZET(dimension_idx);

nmatrix* result = ALLOC(nmatrix);

result->dtype = input->dtype;

result->stype = input->stype;

result->count = (input->count / input->shape[dim_idx]);

result->ndims = (input->ndims) - 1;

result->shape = ALLOC_N(size_t, result->ndims);

for(size_t i = 0; i < result->ndims; ++i) {

if(i < dim_idx)

result->shape[i] = input->shape[i];

else

result->shape[i] = input->shape[i + 1];

}

size_t* lower_indices = ALLOC_N(size_t, input->ndims);

size_t* upper_indices = ALLOC_N(size_t, input->ndims);

for(size_t i = 0; i < input->ndims; ++i) {

lower_indices[i] = 0;

upper_indices[i] = input->shape[i] - 1;

}

lower_indices[dim_idx] = upper_indices[dim_idx] = -1;

for(size_t i = 0; i < input->shape[dim_idx]; ++i) {

lower_indices[dim_idx] = upper_indices[dim_idx] = i;

get_slice(input, lower_indices, upper_indices, result);

rb_yield(Data_Wrap_Struct(NMatrix, NULL, nm_free, result));

}

return self;

}

nm_each_rank can be used to iterate along any dimension. So, nm_each_row, nm_each_column and nm_each_layer would call this function with dimension_idx as 1, 2 and 3 receptively.

VALUE nm_each_row(VALUE self) {

return nm_each_rank(self, SIZET2NUM(0));

}

VALUE nm_each_column(VALUE self) {

return nm_each_rank(self, SIZET2NUM(1));

}

VALUE nm_each_layer(VALUE self) {

return nm_each_rank(self, SIZET2NUM(2));

}

Following are some examples to explain the usage of these iterators. Alternatively, one can use m.each_rank(0) in place of m.each_row, m.each_rank(1) in place of m.each_column, m.each_rank(2) in place of m.each_layer and it would work the same.

pry -r './lib/nmatrix.rb'

[1] pry(main)> m = NMatrix.new [2, 4], [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

=>

[2] pry(main)> m.each_row do |x|

[2] pry(main)* p x.elements

[2] pry(main)* end

[1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0] #first row

[5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0] #second row

=>

pry -r './lib/nmatrix.rb'

[1] pry(main)> m = NMatrix.new [2, 4], [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

=>

[2] pry(main)> m.each_column do |x|

[2] pry(main)* p x.elements

[2] pry(main)* end

[1.0, 5.0] #first column

[2.0, 6.0] #second column

[3.0, 7.0] #third column

[4.0, 8.0] #fourth column

=>

pry -r './lib/nmatrix.rb'

[1] pry(main)> m = NMatrix.new [2, 2, 2], [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

=>

[2] pry(main)> m.each_layer do |x|

[2] pry(main)* p x.elements

[2] pry(main)* end

[1.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.0] #first layer

[2.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0] #second layer

=>

Corresponding pull requests can be found here at https://github.com/SciRuby/numruby/pull/19 and https://github.com/SciRuby/numruby/pull/22.

For coming weeks, I’ll work on implementing broadcasting and start working on LAPACK functionalities. Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments section. Thanks for reading.